Thinking of traveling abroad next year? You might want to steer clear of Afghanistan, Mali, Syria, Iraq and Ukraine, which rank among the world’s most dangerous destinations for business and pleasure travelers.

That’s according to this year’s “Travel Risk Map,” compiled by global security and medical specialists from the risk assessment firm International SOS.

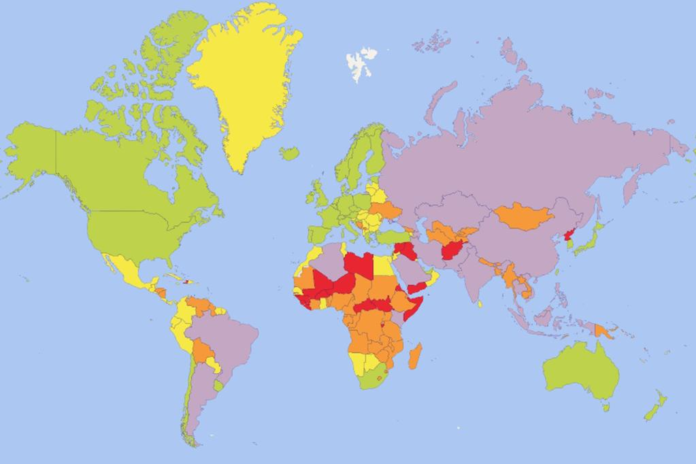

The index takes into account countries’ security levels based on the threat posed to employees by political violence (including terrorism, insurgency, politically motivated unrest and war); social unrest (such as sectarian, communal and ethnic violence); and violent and petty crime, among other factors, per the agency’s site.

The most “extreme risk” countries for 2023 in terms of security include Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Mali, Iraq and Ukraine. These nations were targeted for “minimal or non-existent” government control and law across large regions, as well as “serious threat of violent attacks by armed groups targeting travelers and international assignees,” per the site.

The index weighs a country’s political violence, social unrest and crime. International SOS

Afghanistan was ranked an “extreme risk” country in terms of security. AFP via Getty Images

Once ranked a “medium risk” country, Ukraine was upgraded to “extreme risk” after getting invaded by Russia in February. Over the weekend, Ukrainian nationals fled the city of Kherson after sustained Russian shelling rendered the area virtually unlivable.

Meanwhile, “low risk” countries include the US, Canada, China, Australia and most of Europe, while Scandinavian nations constituted the highest number of “insignificant” risk nations — the safest designation. In fact, Europe saw virtually no overall increase in security risk despite the Ukraine-Russia conflict and its resulting economic upheaval, Metro reported.

The firm also assessed nations’ medical safety as it pertains to business travel, rating countries on everything from COVID-19 healthcare to the infectious disease standards of emergency medical services and access to quality pharmaceutical supplies.

Clocking in at “low risk” in the medical category are the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and most of Western Europe. Meanwhile, “very high risk” nations include Mali, Niger, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan, North Korea, Somalia and Haiti.

A man shows a child a destroyed Russian military truck on display in central Kyiv, Ukraine. Oleksii Chumachenko / SOPA Image

For the first time since the map’s creation in 2015, the International SOS factored in countries’ mental health based on research from the Global Burden of Disease Study. The index counts anxiety, depression, eating disorders and schizophrenia as mental health disorders.

Interestingly, many countries that scored well in the medical safety and security categories ranked poorly in terms of mental health and vice versa. According to the index, between 15 and 17.5% of people have experienced mental health issues in Western Europe and most of Scandinavia. Meanwhile, a whopping 17.5 to 20% — the highest amount — have suffered these problems in Greenland, Spain, Australia and New Zealand.

Iran also scored poorly in the mental health category, which experts attributed to the nation’s strict morality laws. On Tuesday, a man was killed by Iranian security forces for allegedly celebrating the country’s World Cup loss to the US amid nationwide protests against the regime.

Syria was rated an “extreme risk” nation in terms of security. AFP via Getty Images

Meanwhile, mental health issues have been on the rise internationally with around one in seven people globally (some 11-18%) suffering one or more mental or substance use disorders, per the World Health Organization.

Though specific factors aren’t cited, COVID-19 could be partially to blame as the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25% in the first year of pandemic, according to WHO.

“With travel and health risks on the rise in many regions, it is important for organizations to also focus on mitigating the ongoing impact of mental health issues,” Dr. Irene Lai, medical director at International SOS, said in a statement.

“Although other acute medical issues which may have a significant impact regularly arise, mental health problems remain in the background and cannot be overlooked.”

Most dangerous places to travel in 2023 revealed

Recent Comments

on Dozens of boats cruise the Seine in a rehearsal for the Paris Olympics’ opening ceremony on July 26

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on If you’re a frequent traveler, these wrap tops from Aday will revolutionize your on-the-go wardrobe

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on Sports World Hails ‘Superwoman’ Lindsey Vonn for Her Grand Comeback Despite Career-Changing Injury

on How Does Jack Nicklaus Travel? Exploring the Private Jets Owned by the ‘Golden Bear’ Over the Years

on College basketball rankings: Kansas helps Big 12 lead conference race for most Top 100 And 1 players

on A weaker dollar, skyrocketing prices and ‘record’ visitor numbers: Good luck in Europe this summer

on Lamar Jackson: NFC side tipped to be ‘overwhelming’ Super Bowl favourites if they signed Ravens QB

on ICC T20 World Cup 2022: “Love Cricket At All Levels, I’ll Watch Any Cricket, And Love Going There”

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on Joe Manchin and Tommy Tuberville introduce bill on name, image and likeness rules for college sports

on San Mateo County Community College District sues five companies over role in ‘pay to play’ scandal

on If you’re a frequent traveler, these wrap tops from Aday will revolutionize your on-the-go wardrobe

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on Biden to tout bill’s prescription drug prices, energy provisions in pitch to Americans, aide says

on Following Exchange With Caitlin Clark At News Conference, Columnist Won’t Cover Indiana Fever Games

on Inside Out Mini Jawbreaker Puzzle Game from Disney Cruise Line Now Available at Walt Disney World

on Katherine Paprocka allegedly embezzled nearly $600k from school for family vacations, IVF treatment

on Johnny Knoxville Talks Jackass Stunts And How They Compare To Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible Work

on Napoli owner admits he ‘knew’ Victor Osimhen would end up at ‘Real Madrid, PSG or one English club’

on Camilla Parker Bowles Revealed the ‘Nicest Thing’ She and Prince Charles Do When They Travel Is Free

on Russian cruise and ballistic missiles kill 4 in Ukraine and Ukrainian rockets kill 2 in Russian city

on Can Tom Cruise Save The Box Office Again With Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning? An Investigation

on Boise State vs. Air Force live stream, odds, channel, prediction, how to watch on CBS Sports Network

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on College basketball rankings: Kansas helps Big 12 lead conference race for most Top 100 And 1 players

on Inside Floyd Mayweather’s Lavish Lifestyle: A Look at His Stunning Car Collection and Private Jet

on Cruise guest gets stuck on ‘claustrophobic’ water slide suspended over ocean: ‘That is super scary’

on David and Victoria Beckham so ‘Charmed’ by Tom Cruise They Have His Photos on Display at Their Home

on Boston College vs. Army live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on Big Tech companies will cover travel expenses for employees’ medical procedures, including abortion

on Russian cruise and ballistic missiles kill 4 in Ukraine and Ukrainian rockets kill 2 in Russian city

on A weaker dollar, skyrocketing prices and ‘record’ visitor numbers: Good luck in Europe this summer

on GameFly Sale Offering Nintendo Switch Sports at a Mind-Blowing Price, Don’t Miss the Opportunity!

on Ford Blue Cruise: US regulators investigate fatal crashes involving hands-free driving technology

on San Mateo County Community College District sues five companies over role in ‘pay to play’ scandal

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on Despite strong Lunar New Year holiday data, consumer spending in China isn’t roaring back just yet

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on Devout athletes find strength in their faith. But practicing it and elite sports can pose hurdles

on The Rev. Al Sharpton to lead protest after Florida governor’s ban of African American studies course

on After UFC Fallout, Conor McGregor Offers a Valuable Piece of Advice to Free Agent Francis Ngannou

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on Saipan, placid island setting for Assange’s last battle, is briefly mobbed – and bemused by the fuss

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on David and Victoria Beckham so ‘Charmed’ by Tom Cruise They Have His Photos on Display at Their Home

on Iowa State starting RB Jirehl Brock among latest college football players charged in gambling probe

on Biden to tout bill’s prescription drug prices, energy provisions in pitch to Americans, aide says

on Iowa State starting RB Jirehl Brock among latest college football players charged in gambling probe

on The Rev. Al Sharpton to lead protest after Florida governor’s ban of African American studies course

on Sports World Hails ‘Superwoman’ Lindsey Vonn for Her Grand Comeback Despite Career-Changing Injury

on San Mateo County Community College District sues five companies over role in ‘pay to play’ scandal

on Saipan, placid island setting for Assange’s last battle, is briefly mobbed – and bemused by the fuss

on ‘Pokémon Scarlet’ and ‘Violet’ Fan Theories Suggest Legendary Time Travel, Alternate Dimension Plot

on Joe Manchin and Tommy Tuberville introduce bill on name, image and likeness rules for college sports

on Inside the Michael Jordan ‘Air’ movie, plus why NFL, others are buying into the sports film industry

on If you’re a frequent traveler, these wrap tops from Aday will revolutionize your on-the-go wardrobe

on How Does Jack Nicklaus Travel? Exploring the Private Jets Owned by the ‘Golden Bear’ Over the Years

on Hollywood Reporter: Tom Cruise negotiated with movie studios over AI before the actors strike began

on Ford Blue Cruise: US regulators investigate fatal crashes involving hands-free driving technology

on Dozens of boats cruise the Seine in a rehearsal for the Paris Olympics’ opening ceremony on July 26

on Devout athletes find strength in their faith. But practicing it and elite sports can pose hurdles

on Despite strong Lunar New Year holiday data, consumer spending in China isn’t roaring back just yet

on David and Victoria Beckham so ‘Charmed’ by Tom Cruise They Have His Photos on Display at Their Home

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on CBS Sports announces Matt Ryan will join NFL studio show. Longtime analysts Simms and Esiason depart

on Boston College vs. Army live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on Boise State vs. Air Force live stream, odds, channel, prediction, how to watch on CBS Sports Network

on Biden to tout bill’s prescription drug prices, energy provisions in pitch to Americans, aide says

on After UFC Fallout, Conor McGregor Offers a Valuable Piece of Advice to Free Agent Francis Ngannou

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on ‘Best Intention’: Chris Kirk Has Absolute Trust in Jay Monahan and PGA Tour’s Widely Debated Model

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CBS Sports announces Matt Ryan will join NFL studio show. Longtime analysts Simms and Esiason depart

on Carlos Sainz’s Soccer Fanboy Emerges as Spaniard Shares Defining Moment With This Real Madrid Legend

on Biden: ‘At this point I’m not’ planning to visit East Palestine, Ohio, after toxic train derailment

on ‘Best Intention’: Chris Kirk Has Absolute Trust in Jay Monahan and PGA Tour’s Widely Debated Model

on Ahead of big sports weekend, dispute with Disney leaves millions of cable subscribers in the dark

on A heavy wave of Russian missile attacks pounds areas across Ukraine, killing at least 4 civilians

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on Army vs. Coastal Carolina live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on AL Rookie of the Year Julio Rodriguez Spreads Joy and Sportsmanship to the Youth of Loma de Cabrera

on After UFC Fallout, Conor McGregor Offers a Valuable Piece of Advice to Free Agent Francis Ngannou

on Dubai International Airport sees 41.6 million passengers in first half of year, more than in 2019

on Devout athletes find strength in their faith. But practicing it and elite sports can pose hurdles

on Despite strong Lunar New Year holiday data, consumer spending in China isn’t roaring back just yet

on Dave Portnoy: Taylor Swift’s security should ‘drag Kim Kardashian to jail’ if she attends Eras Tour

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CBS Sports, Serie A announce new TV rights deal; Paramount+ to air over 400 Italian soccer matches

on Cam Newton’s Violent Public Incident Draws Hilarious Reaction From 3x All-Star: “Where Do I Sign Up

on Boston College vs. Army live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on Angel Reese Launches Foundation Dedicated To Empowering Women Through Sports & Financial Literacy

on A weaker dollar, skyrocketing prices and ‘record’ visitor numbers: Good luck in Europe this summer