Editor’s Note: Sign up for Unlocking the World, CNN Travel’s weekly newsletter. Get news about destinations opening and closing, inspiration for future adventures, plus the latest in aviation, food and drink, where to stay and other travel developments.

CNN —

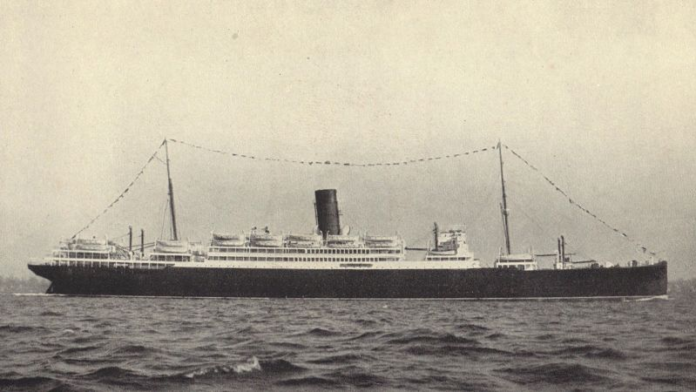

On March 30, 1923, exactly 100 years ago, the world’s first continuous passenger cruise ship arrived back in New York City after completing a 130-day voyage.

This six-month trip was the first of its kind, paving the way for the world cruises of today, taking in destinations including Japan, Singapore, Egypt and India and traversing the Suez and Panama Canals. The voyage took place aboard the SS Laconia, a Cunard passenger liner chartered by the American Express Company for the occasion.

Among the Laconia’s were two twentysomething sisters, Eleanor and Claudia Phelps. Eleanor and Claudia were brimming with excitement as the Laconia left port on November 21, 1922, snapping photographs and jotting down observations in their respective diaries.

While Claudia worried that her journal-keeping would “die halfway to San Francisco” – the Californian city being only the Laconia’s second stop – ultimately, she and Eleanor kept up their travel logs for the duration of the 130-day voyage.

As the Laconia circumnavigated the globe, Eleanor and Claudia, who were traveling with their mother, scribbled down observations, collected souvenirs and took photographs, pasting them in their leather-bound diaries.

Today, the Phelps sisters’ Laconia collection, which includes their travel diaries, photographs, slides and film footage, is owned by the University of South Carolina’s Moving Image Research Collections.

In the last page of her travel log, Eleanor tried to sum up the experience, but felt she could only come up short: “How can one come to a conclusion or express an opinion on the world as I saw it in 130 days?” she wrote.

New era of travel

This photograph from Eleanor Phelps’ Laconia scrapbook depicts travelers on board as the ship departed New York. Eleanor’s sister Claudia Phelps is in the center. University of South Carolina MIRC

While the Laconia was built to accommodate some 2,200 passengers, American Express restricted passenger numbers on the 1922-23 world cruise to just 450. No traveler would be sleeping below deck in third class. There’d be no overcrowding. The aim was a luxurious experience, setting a new bar for travel for those with means.

The Phelps sisters hailed from a wealthy, South Carolina-based family who’d made their fortune from a mix of flour mills, fine china, railways and politics, according to Stephanie Wilds, Eleanor Phelps’ granddaughter and Claudia Phelps’ great niece.

“It’s all blue blood money, old American aristocratic wealth,” Wilds tells CNN Travel today.

The opening entry in Eleanor Phelps’ travel diary. University of South Carolina MIRC

While Wilds insists “it wasn’t a lot of money, it was mostly prestige,” the Phelps family had the funds to afford three tickets on the Laconia.

Wilds says Eleanor and Claudia’s mother hoped her daughters might meet some eligible bachelors on board the ship – she saw the voyage as her daughters “coming out” into society.

“My great grandmother was trying to introduce her daughters to proper suitors,” says Wilds.

Much in the manner of cruises today, there was plenty of opportunity for mingling on board and plenty of spaces in which to do so. In her diary, Claudia describes the Laconia’s “charming black oak smoking room and a very pretty dining room with beautifully sparkling glass and silver.”

Eleanor writes of on-board leisure activities including lectures on the history and language of the Laconia’s destinations, a “camera club” – perfect for the Phelps sisters and their interest in photography – as well as a costume ball and classical concerts.

A glimpse inside one of the SS Laconia’s passenger cabins. Cunard

Meanwhile, Claudia details on-board clay pigeon shooting, fencing classes and time spent working out in the on-board gym.

Claudia and Eleanor describe some interaction with other passengers, but it’s not obvious that they were interested in meeting eligible suitors – the primary focus of their diaries is the countries they visit, punctuated by descriptions of the ever-changing ocean sunsets and sunrises.

Eleanor’s diary, which is available to view as part of the University of South Carolina’s collection, includes newspaper cuttings – a New York Times article entitled “Ship starts ‘round world trip” – passenger information handouts from American Express detailing the day’s schedules, and memorabilia collected in ports, including stamps and bank notes.

Crossing the Panama Canal

The Laconia didn’t visit everywhere on Earth – it didn’t reach Australian waters, for example – but it was a voyage unlike any that came before it.

In November 1923, the Laconia was the first ocean liner to traverse the Panama Canal, then just a decade old. Eleanor describes waking up “in the early morning mist” so as not to miss a moment of the crossing.

“The sky was all covered with soft clouds, tinted in light greys and violets, and out at sea the descent of rain in patches looked like gauzy veils of silver,” she writes.

Eleanor’s primary impression of the canal itself was “the beauty of it.” She writes of “the cleanness and finish of the concrete work, the freshness of the green, the artistic effect of the planning and the evident thought for contour lines in the laying out of houses and streets.”

In her diary, she pasted an information booklet, dated November 1922, which describes the Panama Canal’s construction, and the distances saved by ships taking that route.

Another page from Eleanor Phelps’ scrapbook, featuring photographs she took in Japan. University of South Carolina MIRC

Other highlights include Claudia’s description of her first glimpse of Mount Fuji, in Japan: “Its perfect cone, snow clad, glowing a soft gold through the haze. I can imagine no lovelier view than our first one and now know why the Japanese consider it sacred,” she writes.

Often Eleanor and Claudia struggle for words. Eleanor says that her expectations of India’s Taj Mahal were “high, but were so far exceeded that there are no words, no possible means of expression.”

She concludes: “Nothing could possibly do it justice and so I shan’t try.”

Here’s a stunning photograph of Darjeeling, India, pasted into Eleanor Phelps’ scrapbook. University of South Carolina MIRC

At each port American Express offered the Laconia passengers guided excursions and tours, on site hotel stays and the chance to soak up local culture.

Claudia writes of Darjeeling, India: “We climbed through forests after going through a village, getting gorgeous views of the valleys bathed in silver light and with veils of silver brushing against the mountains. We reached the top just as dawn was breaking, had coffee and climbed the round observation tower to see the sun rise.”

A ‘travel legacy’

The title page of Eleanor Phelps’ scapbook. The document is now owned by the University of South Carolina. University of South Carolina MIRC

As wealthy Americans traveling in 1923, the Phelps sisters’ observations are sometimes jarring to a modern reader, but granddaughter and great niece Stephanie Wilds argues that overall the sisters traveled with an “open-mind.”

“I appreciate their curiosity and their tolerance. They just approached things with a very good humor, for the most part,” she says. “I just think that’s just kind of wonderful. I think that’s how people ought to travel, curious, open minded, tolerant. That’s how we ought to approach the world.”

Growing up, Wilds was close to her great aunt Claudia, whom she says upheld that attitude throughout her life and myriad travels.

“She had a great sense of humor, and a fair amount of humanity – and so she was not worrying about how comfortable she was or how well she was treated. She was really looking at the people,” says Wilds.

As a child, Wilds was enthralled by stories Claudia shared of the Laconia voyage.

“She remembered many little, tiny details of children playing, and snake charmers, and she loved animals, so she told us all about riding camels and riding elephants. That’s what she got out of it, she loved the cultural experience.”

But although Wilds recalls hearing these stories when she was a child, and marveling over the glass slides on display in Claudia’s house, it was only when her great aunt passed away in the 1980s and Wilds inherited Claudia and Eleanor’s Laconia memorabilia that she fully appreciated her heritage.

Wilds particularly loves their photographs and slides – she isn’t sure how the Phelps sister came to be keen photographers, but she also has an early “selfie” of her great aunt, taken with a box camera when she was around 16.

Looking through the photos and diaries as an adult, Wilds is also better able to consider the interesting juncture at which the Laconia’s 1922-1923 voyage took place.

The cruise came just a few years after the world and its borders were disrupted by the First World War. The Laconia seemed to usher in a new era – that winter, several other passenger liners followed the Laconia on subsequent world voyages.

But this was also a fleeting moment in time. Less than 20 years later, the Second World War ground passenger cruise travel to a halt. The SS Laconia was requisitioned for the US war effort and was sunk off the coast of western Africa in 1942.

While cruise travel recommenced post-war, Wilds sees the Laconia’s 1922-1923 voyage as a specific moment in history.

“It was the roaring 20s,” she says. “It was that wonderful window.”

Wilds says the Phelps sisters left her family a “travel legacy.” She looks back fondly on a childhood trip with her great aunt Claudia around the Mediterranean. And Wilds also experimented with cruise travel, including crossing the Atlantic on the Queen Elizabeth II cruise ship.

“My brother lives in Japan. We’ve all traveled around the world. My mother has been to Indonesia probably half a dozen times,” adds Wilds.

Today, when she talks about her family’s time on the Laconia, Wilds says she gets mixed reactions. Some people are fascinated by an insight into travel 100 years ago, others see the diaries and photographs as unfortunate remnants of a time when travel was mostly confined to wealthy White travelers.

“It gets into sort of a class thing,” says Wilds.

But Wilds thinks Eleanor and Claudia’s travel diaries and photographs offer a fascinating insight into travel in years gone by. She was excited to donate the documents to the University of South Carolina some years ago.

“I’m always pleased that they were on the Laconia and that they had that experience and that they were able to share that legacy. And here 100 years later, we’re still talking about it. I think that’s pretty marvelous,” she says.

What it was like on board the first ever round-the-world world passenger cruise

Recent Comments

on Iowa State starting RB Jirehl Brock among latest college football players charged in gambling probe

on The Rev. Al Sharpton to lead protest after Florida governor’s ban of African American studies course

on Sports World Hails ‘Superwoman’ Lindsey Vonn for Her Grand Comeback Despite Career-Changing Injury

on San Mateo County Community College District sues five companies over role in ‘pay to play’ scandal

on Saipan, placid island setting for Assange’s last battle, is briefly mobbed – and bemused by the fuss

on ‘Pokémon Scarlet’ and ‘Violet’ Fan Theories Suggest Legendary Time Travel, Alternate Dimension Plot

on Joe Manchin and Tommy Tuberville introduce bill on name, image and likeness rules for college sports

on Inside the Michael Jordan ‘Air’ movie, plus why NFL, others are buying into the sports film industry

on If you’re a frequent traveler, these wrap tops from Aday will revolutionize your on-the-go wardrobe

on How Does Jack Nicklaus Travel? Exploring the Private Jets Owned by the ‘Golden Bear’ Over the Years

on Hollywood Reporter: Tom Cruise negotiated with movie studios over AI before the actors strike began

on Ford Blue Cruise: US regulators investigate fatal crashes involving hands-free driving technology

on Dozens of boats cruise the Seine in a rehearsal for the Paris Olympics’ opening ceremony on July 26

on Devout athletes find strength in their faith. But practicing it and elite sports can pose hurdles

on Despite strong Lunar New Year holiday data, consumer spending in China isn’t roaring back just yet

on David and Victoria Beckham so ‘Charmed’ by Tom Cruise They Have His Photos on Display at Their Home

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on CBS Sports announces Matt Ryan will join NFL studio show. Longtime analysts Simms and Esiason depart

on Boston College vs. Army live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on Boise State vs. Air Force live stream, odds, channel, prediction, how to watch on CBS Sports Network

on Biden to tout bill’s prescription drug prices, energy provisions in pitch to Americans, aide says

on After UFC Fallout, Conor McGregor Offers a Valuable Piece of Advice to Free Agent Francis Ngannou

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on ‘Best Intention’: Chris Kirk Has Absolute Trust in Jay Monahan and PGA Tour’s Widely Debated Model

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CBS Sports announces Matt Ryan will join NFL studio show. Longtime analysts Simms and Esiason depart

on Carlos Sainz’s Soccer Fanboy Emerges as Spaniard Shares Defining Moment With This Real Madrid Legend

on Biden: ‘At this point I’m not’ planning to visit East Palestine, Ohio, after toxic train derailment

on ‘Best Intention’: Chris Kirk Has Absolute Trust in Jay Monahan and PGA Tour’s Widely Debated Model

on Ahead of big sports weekend, dispute with Disney leaves millions of cable subscribers in the dark

on A heavy wave of Russian missile attacks pounds areas across Ukraine, killing at least 4 civilians

on 2024 Super Bowl: CBS Sports Network and CBS Sports HQ to combine for 115 hours of weeklong coverage

on 2023 NFL All-Rookie Team: CBS Sports draft expert, former GM unveil league’s best first-year players

on Army vs. Coastal Carolina live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on AL Rookie of the Year Julio Rodriguez Spreads Joy and Sportsmanship to the Youth of Loma de Cabrera

on After UFC Fallout, Conor McGregor Offers a Valuable Piece of Advice to Free Agent Francis Ngannou

on Dubai International Airport sees 41.6 million passengers in first half of year, more than in 2019

on Devout athletes find strength in their faith. But practicing it and elite sports can pose hurdles

on Despite strong Lunar New Year holiday data, consumer spending in China isn’t roaring back just yet

on Dave Portnoy: Taylor Swift’s security should ‘drag Kim Kardashian to jail’ if she attends Eras Tour

on CONCEPT ART: New Details Revealed for Disney Cruise Line Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point Destination

on “Completely Knocked Me Out”: Rob Lowe Recalls Boxing Match With Tom Cruise On 1983 Brat Pack Classic

on CBS Sports, Serie A announce new TV rights deal; Paramount+ to air over 400 Italian soccer matches

on Cam Newton’s Violent Public Incident Draws Hilarious Reaction From 3x All-Star: “Where Do I Sign Up

on Boston College vs. Army live stream, how to watch online, CBS Sports Network channel finder, odds

on Angel Reese Launches Foundation Dedicated To Empowering Women Through Sports & Financial Literacy

on A weaker dollar, skyrocketing prices and ‘record’ visitor numbers: Good luck in Europe this summer